Modern Art and the Death of a Culture

Nov 06, 2013 by Bonnie

That’s the name of a 1970 book by H. R. Rookmaaker. I’ve never read the book, and although I’d like to read it someday, in a way the title says it all. One doesn’t need to be an art expert to see a connection between the death of civilization and the gradual degradation of all the artistic media as culture has become divorced from the meaning and purpose that comes from being children of God. Our experiences in the world of art one day really reinforced this conclusion.

While in Houston, we took one day to see some free works of art. The first was a beer can house which is a piece of folk art covered with beer cans, bottles, and other beer paraphernalia; the “fences,” walkways, and driveway are made of beer can lids, marbles, and pieces of glass bottles embedded in concrete. John Milkovisch worked through the late 1960s to transform his home. The house is estimated to include over 50,000 beer cans. Today, the house is owned and operated by The Orange Show Center for Visionary Art, founded to preserve and present works of extraordinary imagination. Milkovisch didn’t see it so grandly. He said he did it because he didn’t want to mow the yard.

Next we visited a free art museum which features the art collection of John and Dominique de Menil. Also on the grounds, founded by the Menils, was the Rothko Chapel, featuring fourteen large paintings by artist Mark Rothko covering the walls of the octagonal chapel.

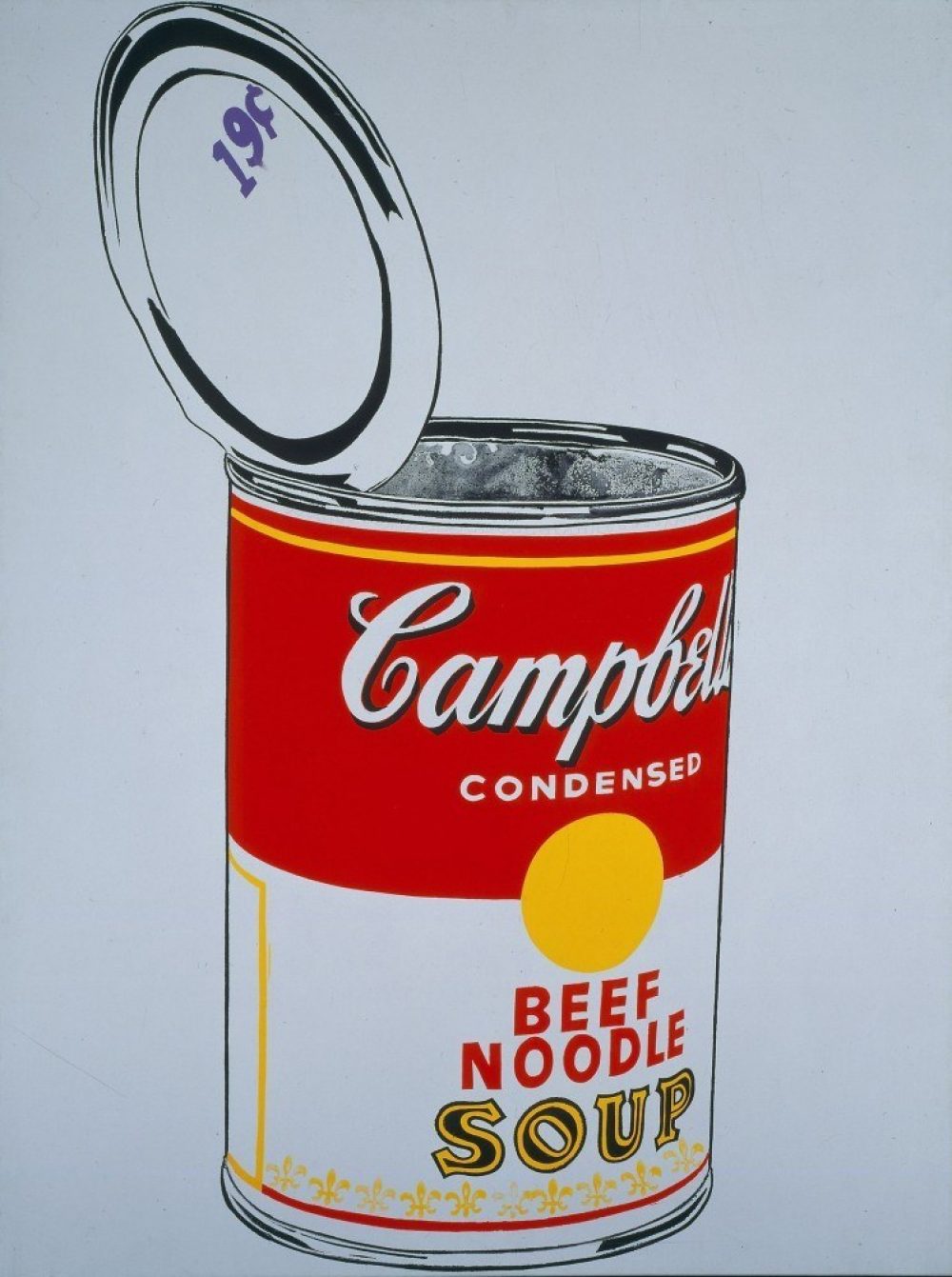

Different portions of the Menils’ huge 20th century art collection are on display at any given time, including surrealism, pop art, and varieties of other abstract art. There are also several galleries of Byzantine, Medieval, and Tribal antiquities, which was a little like seeing a missionary curio display; there were works from several areas we recognized, such as Irian Jaya and West Africa. We enjoyed seeing one of Andy Warhol’s soup can canvases, which was displayed next to another of his works, Electric Chair. We also saw Picasso’s Woman in a Red Armchair, defaced by a museum visitor in 2012 but restored and is back on display.

Modern art always says something to me, but very often it speaks despair and the meaninglessness of life. Despite a few uplifting pieces (mostly ethnic art), I left the museum saddened by the messages I was feeling from the art I had seen. But I looked forward to seeing the Rothko Chapel. I didn’t expect it to reflect any particular religion, but even so, I was not prepared for what I actually saw.

The chapel is a plain, octagonal building. As you enter, the staff points you to one of the two entrances to the chapel itself. As you go around the corner, you see a bench with holy books of many different religions displayed. I’m assuming it’s OK to pick one up and take it in with you while you meditate. Then you enter the chapel itself. Even though I had seen some of Rothko’s works in the museum, I was not prepared for what I saw in the chapel. There were triptychs on three walls, and single paintings on the other five. All fourteen were solid black. There were minor variations, but the bottom line was darkness. There were benches in the middle, so that folks could sit and contemplate either the paintings or their own feelings. The staff encouraged quietness and reverence for what we were seeing, and were very watchful, to make sure that none of the masterpieces were harmed by someone accidentally leaning against one. In fact, one staff woman came over and quietly asked Art to please step away from the wall because she was afraid he was getting too close and might accidentally lean back on the artwork. Art complied by willingly and joyfully stepping completely out of the chapel.

We didn’t stay long. We didn’t even want to sit down. The impact was huge, but we couldn’t talk about it until we got outside. As we talked, we realized that in trying to come to common ground between all religions, the only conclusion Rothko could draw was nothingness and darkness. I was overtaken with a profound sadness for people who revere meaninglessness above all things. I was reminded of the old story about the emperor’s new clothes—everyone waxing eloquent about nothingness.

As I was doing research for this article, I discovered that Mark Rothko did not live to see the chapel’s completion in 1971. After a long struggle with depression, he committed suicide in his New York studio on February 25, 1970. Was anyone hearing the messages in his art? Did they offer hope?

I was reminded once again that the only hope for the human soul is an encounter with the God who loves us so much that He not only revealed Himself to us in Christ, but also redeemed us and took us off the path to destruction which is the logical end of human nature, as communicated by modern art.